How Often Are Aston Martins being Stolen in the UK?

What the Data Actually Shows

Editor’s Introduction - Dan, Fuel the Passion

Over the past year or so, it’s been hard to avoid stories about vehicle theft in the UK.

Television programmes, news reports and industry commentary have increasingly highlighted organised car crime, with particular focus on vehicles believed to be stolen to order and shipped overseas.

That wider context suddenly became uncomfortably personal over the festive period, when a friend of mine, an Aston Martin owner, had his home broken into. The car itself was not taken, but that detail almost feels secondary. The violation of someone entering your home uninvited, the sense of safety stripped away in an instant, lingers far longer than any physical loss. Even when the outcome is “fortunate,” the experience is deeply unsettling and leaves you questioning what might have happened, rather than what did. It was that moment, not hypothetical, not abstract, that led to a very simple, very human question: How often are Aston Martins actually stolen in the UK?

Rather than speculate, or rely on anecdote, I decided to look for evidence. The result was a series of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to establish what the official data actually says, and, just as importantly, what it doesn’t.

This article sets out those findings based on official data and transparent sources.

“This article is built on Freedom of Information responses, not assumptions.”

Vehicle Theft in the UK: The Wider Context

Vehicle theft in the UK is a real and well-documented issue. National statistics published by bodies such as the Office for National Statistics and the DVLA show that, following the pandemic years, overall vehicle theft rose sharply, peaking around 2023 before easing slightly more recently. Even with that easing, theft levels remain materially higher than they were a decade ago. This broader trend explains why vehicle crime has become more prominent in public discussion. It also explains why prestige and performance cars often attract disproportionate attention in media reporting.

High values, international demand and organised criminal networks make for compelling headlines. But headlines alone do not tell us how individual marques are actually affected.

The realities of modern vehicle theft have also been brought into the public eye through independent investigations, most notably in a widely viewed YouTube film by Mark McCann (see below). His pursuit of a stolen BMW exposed the speed, organisation and technical sophistication behind today’s car thefts and highlighted how recovery often depends on CCTV, public tip-offs and sheer persistence rather than predictable enforcement.

While anecdotal, the film provides a visual counterpart to the official data, reinforcing just how difficult stolen vehicle recovery can be once a car has left the driveway.

To understand Aston Martin’s position within this wider landscape, national-level data is essential.

Why Look to Freedom of Information Data?

When assessing theft trends by brand, Freedom of Information data is invaluable. It is not perfect, no crime dataset ever is, but it is verifiable, repeatable and grounded in official records rather than assumption.

For this research, FOI requests were submitted to the DVLA and to selected UK police forces.

The DVLA response is particularly important, as it provides a consistent national picture of vehicles recorded as stolen, broken down by make, year and reporting police force.

Local police FOI responses can add context, but they do not replace the value of a national dataset. In this case, the DVLA data forms the backbone of the analysis.

Aston Martin Theft: What the DVLA Data Shows

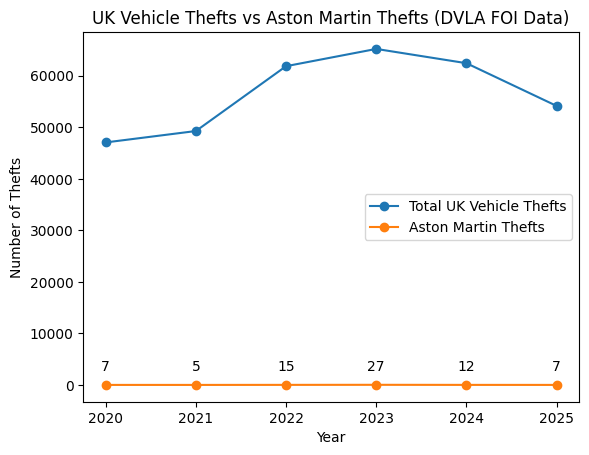

According to DVLA FOI data covering calendar years 2020 through to 2025 (year-to-date), the number of Aston Martin vehicles recorded as stolen in the UK is strikingly low in absolute terms.

Across the entire period, annual thefts range from single digits in the early years to a peak of just 27 vehicles nationally in 2023, before falling again thereafter.

When set against total UK car theft volumes, which run into the tens of thousands per year, Aston Martin thefts represent only a tiny fraction of overall vehicle crime.

The contrast is immediate and instructive. Even at their highest point, Aston Martin thefts account for only a fraction of one per cent of all vehicles recorded as stolen in the UK.

For clarity and reference, the year-by-year figures are shown below.

“As a UK Aston Martin owner, your chance of having your car stolen in any given year is about 0.05% — roughly 1 in 2,000.”

Geography Matters: Where Theft Is, and Isn’t Occurring

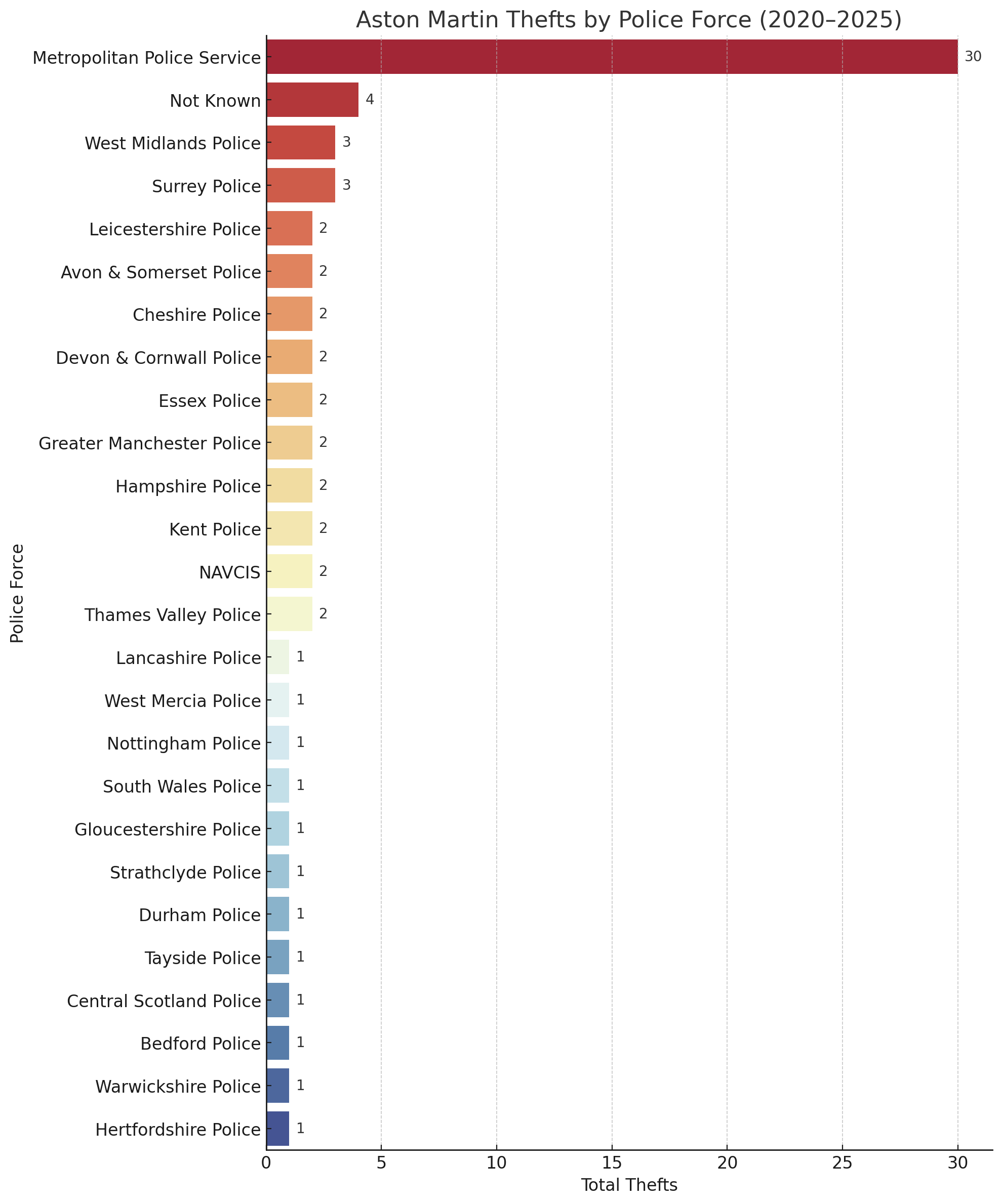

The DVLA data also allows Aston Martin thefts to be examined by reporting police force. This reveals an important pattern: theft is not evenly distributed across the UK.

A significant proportion of recorded Aston Martin thefts are concentrated within the Metropolitan Police area. Outside London, most police forces record either zero or very small numbers of Aston Martin thefts in any given year. This national picture is reinforced by local FOI responses. West Yorkshire Police, for example, confirmed that they recorded no Aston Martin vehicle thefts at all across the period from 2020 to 2025.

The implication is not that Aston Martins are immune from theft in certain regions, but that risk is highly localised and shaped by factors such as population density, organised crime activity and proximity to major transport routes.

What Happens After Theft? Recovery Rates

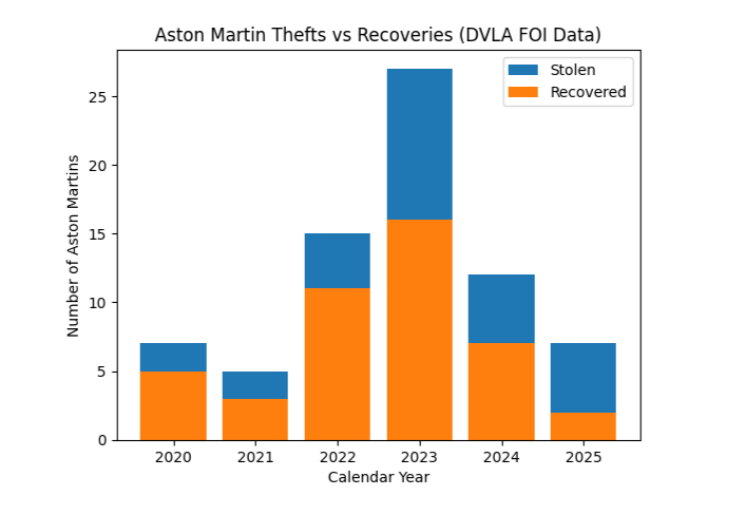

Theft numbers alone never tell the full story. What happens after a vehicle is stolen is just as important.

DVLA FOI data also records whether stolen vehicles are later marked as recovered. For Aston Martin, recovery rates are relatively high across the period studied. In several years, more than half of stolen vehicles were subsequently recorded as recovered.

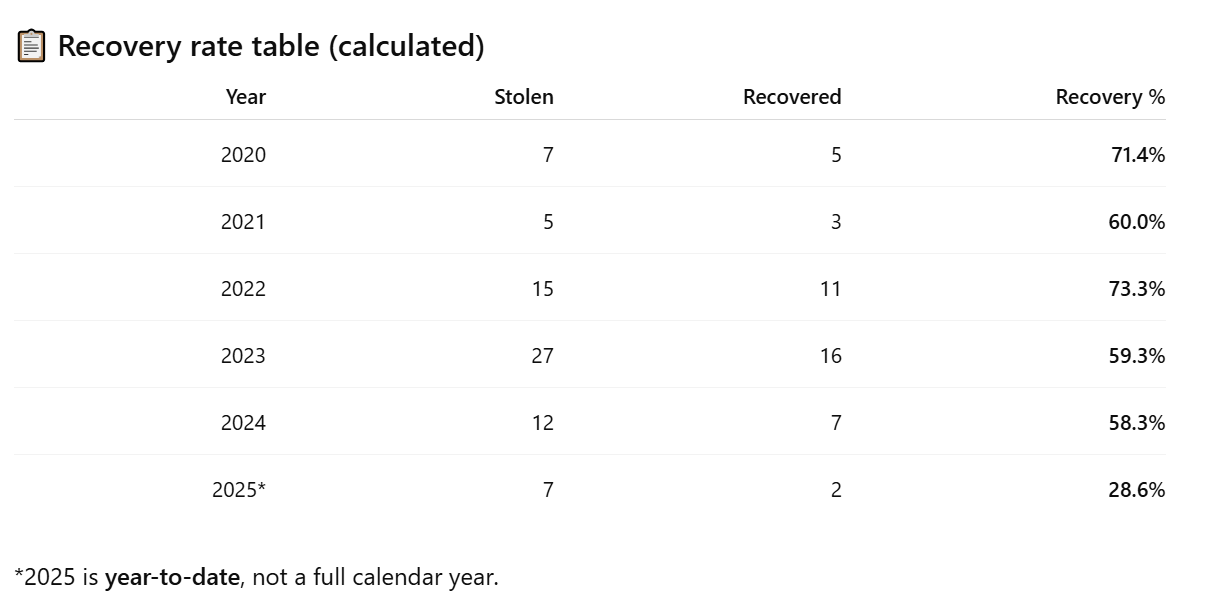

Across the period from 2020 to year-to-date 2025, DVLA data shows that 73 Aston Martins were recorded as stolen in the UK, of which 44 were subsequently recorded as recovered.

“Close to four in every ten stolen Aston Martins were not recovered.”

This equates to an overall recovery rate of just over 60 per cent, meaning that close to four in every ten stolen Aston Martins were not recovered. While this aggregate figure suggests a majority of vehicles do reappear, it masks notable year-to-year variation and should be read with caution, particularly for 2025, which represents partial-year data only. Crucially, the figures also do not indicate the condition in which recovered vehicles were found, nor whether they were economically repairable.

However, high recovery rates do not mean theft is inconsequential.

Even when a vehicle is recovered, the experience can be deeply unsettling for the owner involved. Many owners find that their relationship with the car changes following a theft, particularly where there has been damage, signs of forced entry, or uncertainty about how the vehicle was treated while it was out of their possession.

In some cases, recovered vehicles require extensive cosmetic or mechanical work to return them to their prior condition.

Others become the subject of prolonged discussions with insurers over repair scope, residual value or future cover. For some owners, the emotional impact alone is enough to prompt a decision to sell the car, regardless of whether it can be repaired.

Recovery data therefore provides important context when assessing theft at a national level, but it cannot capture the personal, financial and emotional consequences experienced by individual owners.

“A Range Rover is 24 times more likely to be stolen than an Aston Martin”

Security, Trackers and Careful Inference

A natural question follows: why are Aston Martin theft volumes low and recovery rates comparatively high?

Aston Martin does not publish tracker fitment rates, and DVLA datasets do not record the presence of tracking systems directly. However, the observed patterns, low national theft volumes, relatively high recovery rates and strong geographic concentration, are consistent with a vehicle population in which approved tracking systems and layered security measures are commonly fitted.

By way of context, my own Aston Martin Vantage, the FTP Vantage, is fitted with a monitored tracking system operating 24 hours a day.

If the vehicle moves without me present, contact is made immediately.

In the event of a confirmed theft, the tracking provider liaises directly with the police. This is not unusual or exceptional; it is simply part of modern ownership for a prestige performance car.

Speaking to many Aston Martin owners over the past two years, this pattern is consistent. Most report having immobilisers, trackers, or both fitted to their cars. In many cases, such systems are a condition of insurance. In others, they are installed for peace of mind alone. Either way, they reflect a risk-aware ownership culture rather than a response to widespread theft.

It is also worth considering value in broader terms than headline market price alone. Some Aston Martins that have been on the road for a couple of decades, can now be acquired for £25,000–£35,000, which might suggest that advanced security measures are unnecessary. In practice, the opposite is often true. When the cost of specialist repairs, genuine parts, paintwork, and labour is taken into account, the financial exposure associated with a theft, or even a damaged recovery, can far exceed the vehicle’s apparent market value. For this reason, insurers may still require tracking to be fitted, regardless of purchase price.

It is important to be clear about boundaries here. This is inference, not direct measurement. However, it is inference grounded in observed outcomes and real-world ownership practice, rather than assumption and it aligns with established security expectations for prestige performance vehicles in the UK.

Layered Security and Preventing Keyless Theft

While the data focuses on recorded thefts rather than prevention, it is impossible to ignore the role that layered security plays in shaping these outcomes. Vehicle security is often best understood not as a single device or solution, but as a series of overlapping barriers. Factory alarms and immobilisers form the first layer, but additional measures, such as approved trackers, secondary immobilisers, and simple physical deterrents, all add time, complexity and risk for a would-be thief.

One of the simplest and most cost-effective measures remains the use of Faraday pouches for keyless entry fobs, which block radio signals and reduce exposure to relay-based theft.

While no solution is foolproof, these low-cost steps can meaningfully reduce vulnerability, particularly for cars parked on driveways or on the street.

The recovery data explored earlier, reinforces why insurers insist on trackers for prestige cars: when theft does occur, speed of response is often the difference between recovery and permanent loss. In that context, layered security is not about paranoia, but about tipping the odds decisively in the owner’s favour.

Community Outreach: Looking for Specific Examples and the Counter-Examples

As part of this research, Fuel the Passion invited Aston Martin owners across multiple marque-focused online communities to share any experiences of vehicle theft or theft-related incidents. No responses were received.

This does not rule out individual cases, and anecdotal evidence always has limitations. However, the absence of reported experiences aligns closely with official data and with the rarity of Aston Martin theft reflected in DVLA records.

“That does not diminish the impact theft has on those affected”

What the Data Can, and Can’t Tell Us

No dataset is perfect. DVLA and police records capture reported thefts, not attempted thefts, near-misses or incidents resolved before formal recording. They also depend on accurate classification at the point of reporting.

What the data can do is establish scale, proportion and context. On those measures, the picture is consistent: Aston Martin theft in the UK is thankfully rare, geographically concentrated, and frequently resolved, even if the impact on affected owners can be profound.

The Growing Reality of Car Parts Theft and How to Reduce the Risk

Whole-vehicle theft is only part of the modern risk landscape. Increasingly, owners are returning to find their cars partially stripped: bumpers removed, headlights missing, sensors stolen, interiors damaged and windows smashed in the process. These incidents rarely appear as categorised theft statistics, yet their financial, practical and emotional impact can be significant. A vehicle may be left immobilised, unsafe to drive, or facing repair costs that quickly escalate once parts availability, paintwork and labour are taken into account.

Modern cars now incorporate a growing number of high-value external components.

Parking sensors, radar modules, cameras and driver-assistance systems are often housed within bumpers, grilles and mirrors, making them relatively quick to remove for someone with even modest familiarity.

Replacement costs, however, are anything but modest. Individual sensors can cost hundreds of pounds, while complete front-end assemblies; bumper, grille, headlights and associated electronics, can quickly run into several thousands once genuine parts and specialist labour are involved.

That reality became very real for me recently when a single faulty headlight unit, replaced due to condensation issues rather than theft, resulted in a bill of £3,800 fully supplied and fitted (see the video below).

This shift has been reflected in wider UK reporting over recent years, particularly in large urban areas such as London and Birmingham. Media investigations have documented repeated incidents where cars parked overnight, or even for a few hours in city-centre car parks, were stripped of body panels and external components in minutes. In some locations, multiple vehicles were targeted within the same car park over short periods. While many of the affected cars were not luxury models, the pattern is instructive: modern parts theft is driven less by brand prestige and more by speed, resale value and low risk.

Insurance industry data supports this trend. Claims relating to stolen parking sensors, airbags, steering wheels and exterior trim have risen sharply, driven by rising new-part costs and the ease with which stolen components can be resold online. In many cases, vehicles were not broken into at all; thieves simply took what they wanted and left, sometimes causing surprisingly little visible damage beyond the missing parts themselves.

An especially unusual, but increasingly reported, example has been the theft of rear parcel shelves in parts of north London. In several cases, thieves smashed windows solely to remove the retractable covers, leaving owners facing substantial glass replacement costs and long repair delays.

Police have since advised residents in affected areas to remove parcel shelves overnight where practical. The advice may sound counter-intuitive, but it reflects a simple reality: if the item is not present, it cannot be stolen.

For Aston Martin owners, this matters even though whole-vehicle theft remains rare. Specialist components, limited supply chains and high labour costs mean that partial theft can quickly become a major event. A stolen bumper, damaged sensor array or broken window is not an inconvenience measured in days, but potentially weeks or months, depending on parts availability. As with full theft, the emotional impact often outweighs the financial one, the loss of confidence in where the car can be safely left, and the lingering sense of vulnerability that follows.

Reducing the risk of parts theft is therefore less about eliminating it entirely, and more about making a vehicle a less attractive opportunity. Police and insurers consistently point to simple, open-source measures that help. Parking in well-lit, busy areas rather than secluded spots reduces risk, as does using secure or accredited car parks where available. Removing loose or removable items from the vehicle, including parcel shelves in known hotspot areas, reduces temptation and opportunity. It certainly makes you stop and think. If I find myself driving into a city centre in future, preferably not in the Aston Martin, I may even remove the parcel shelf in advance. A precaution that feels faintly ridiculous, yet increasingly understandable.

Where external components are concerned, deterrence matters. Parking with the front of the car close to a wall, hedge or another vehicle can make access to bumpers and grilles more awkward, increasing the time and effort required. There is, of course, a balance to be struck, parking head-on may reduce access to the front of the car, but can leave the rear more exposed instead! But what’s the most expensive option? - no doubt the front end. While no measure is foolproof, even small inconveniences can be enough to discourage opportunistic thieves and prompt them to move on.

Finally, demand plays a role. Police forces and insurers increasingly urge motorists to avoid buying second-hand parts from unverified sources, as online resale markets have made it easier for stolen components to circulate. Using reputable garages and recognised recycled-parts schemes helps reduce demand and, over time, makes parts theft less profitable.

Crucially, this is an area where national vehicle theft statistics offer limited reassurance, not because the risk is exaggerated, but because it is poorly captured by existing datasets. Parts theft sits in the blind spot between vandalism, theft and insurance loss. It reinforces an important point: protecting a car today is not just about preventing it from being driven away, but about reducing its attractiveness as a source of high-value components in the first place!

Conclusion: Evidence Over Assumption

This article did not begin with an assumption, nor with a desire to reassure or alarm. It began with a reasonable question, prompted by wider reporting on vehicle theft in the UK and sharpened by a real-world incident close to home. Like many owners, I realised that while I had a strong sense of how much I valued my Aston Martin, I had very little sense of the actual scale of Aston Martin theft in the UK, or whether it was something owners should genuinely be worried about.

The answer lies not in speculation, but in evidence.

Based on national DVLA Freedom of Information data, Aston Martin vehicles account for a very small fraction of UK vehicle theft. Even at their peak, theft volumes remain low in absolute terms, geographically concentrated, and frequently resolved. That does not diminish the impact theft has on those affected, but it does place the issue in proportion.

“We buy Aston Martins, and other prestige cars, because we love them.”

We love the brand, the model, the marque, often all three. They are not just assets; they are objects of pride, effort and emotional investment. Wanting to protect them is entirely natural. For my own part, researching this data has been quietly reassuring, not because it removes risk, but because it replaces uncertainty with perspective.

Vehicle security is something I think about often: where I park, how I leave the car, whether a location feels too secluded, and how layered security can reduce vulnerability.

None of that changes after reading the data, but the data does help frame those decisions more rationally, rather than emotionally.

It’s often helpful to step back, crunch the numbers, and understand where genuine risk ends and perception begins.

Ultimately, keeping Aston Martin theft figures low is not about complacency; it’s about making these cars difficult to steal in the first place. Thoughtful ownership, appropriate security, and an understanding of how theft actually occurs all play a part.

In a space often dominated by headlines and assumption, the data tells a quieter, more measured story, and one that rewards taking the time to look properly.

I hope you’ve found this piece interesting, informative, and perhaps reassuring. For many of us, our cars mean far more than numbers on a page, and it’s often helpful to replace uncertainty with understanding.

And as they used to say on BBC Crimewatch many years ago: “the crimes discussed here are rare - so please, don’t have nightmares… sleep well.”

Just a thought…

Stories like this inevitably raise a more uncomfortable question, one that many of us quietly think about but rarely talk about openly.

How secure do you feel about your own car?

Have you ever experienced an attempted theft, suspicious behaviour, or that nagging doubt when you’ve walked away and looked back one last time? Do you use additional security measures beyond the factory setup, trackers, immobilisers, steering locks, garage storage, or is peace of mind coming more from where and how you choose to park?

And perhaps most telling of all: does the risk of theft influence how you use your car? Where you leave it. When you take it out. Or whether you enjoy it as freely as you once did. As an example, if I were to drive into a city centre knowing I have to leave the car at some point, I prefer to leave the Aston at home. But to be honest, that’s more about the vehicle being damaged by a careless car parking neighbour and denting the door as they get out of their own car, rather than theft, but researching for this featured article, does make you think!

I’d be genuinely interested to hear your experiences and thoughts in the comments, because this is an issue that affects the ownership experience just as much as performance figures or design ever could.